By Charlotte Mclean, JMI Course Coordinator

The word “swing” in Jazz serves multiple purposes, encompassing the genre itself, its rhythmic essence, the approach of musicians, and the quality of the music itself, sometimes described as “having the Jazz spirit” or “swinging”. But why do some performances possess this quality while others fall short? And is it subjective?

In this Jazz blog, we’ll embark on a journey through the world of swing music by exploring three distinct avenues. First, we’ll delve into the intricacies of swing, uncovering the technicalities of the rhythms. Next, we’ll examine the nuanced approach to individual notes (articulation) and explore what sets an exceptional Jazz musician apart from a good Jazz musician. Finally, practical practice ideas will be provided, tailored for those looking to enhance their skills but unsure of where to begin. Together, we’ll unravel the mysteries of Jazz and swing, offering insights and inspiration for aspiring musicians and aficionados alike.

SWING RHYTHM

At the heart of Jazz lies the distinctive swing rhythm, often described as feeling “offbeat” or “syncopate d”. Unlike the straight rhythms prevalent in Classical or Pop, swing possesses a lilt and bounce that drives the music forward. However, understanding the nuances of Swing and its constituent rhythms requires closer examination. What exactly does “offbeat and bouncy” entail, and which rhythmic elements contribute to the essence of swing?

TRIPLET FEEL

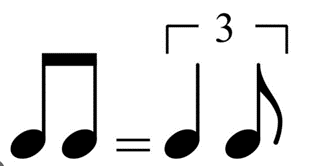

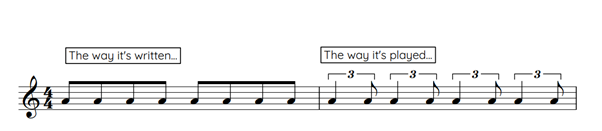

One hallmark of swing rhythms is their triplet feel, often described as a “triplet subdivision” of the beat. Instead of dividing each beat evenly into two (as in straight eighth notes), swing rhythms divide each beat into three, with the first note slightly longer than the second. This asymmetrical division creates a sense of buoyancy and momentum, making it feel “bouncy”.

It’s one thing to play swing rhythms, but quite another to make the entire ensemble truly “swing.” Anyone can play swung eighth-notes, but achieving that elusive quality involves mastering a range of elements, which might initially seem complex and daunting. However, breaking them down reveals key components, all centred around what is often termed “articulation.” This concept revolves around the approach to the rhythms, rather than the rhythms themselves, and it’s crucial for capturing the essence of swing in your music.

VOLUME

Each note is treated as its own entity regarding volume. Instead of a uniform dynamic throughout, musicians vary the volume and attack of each note, creating a dynamic range within phrases and lines. This can be a powerful strategy to give the music life and energy. Take both Jackie McLean and Art Farmer’s solo on Blue Minor for example (On Sonny Clark’s Cool Struttin’ album):

Have a listen to which notes are loud and which notes are soft, and how it gives it a particular feeling. What would these solos sound like if they were “smoother” and didn’t have that variety from note to note?

DURATION

As we can vary the volume from note to note, we can also vary the duration of each note. Similar to volume, the duration of each note is not fixed but subject to improvisation. In Jazz, duration of note is utilised in a way that can be quite pronounced. Listen to Miles Davis on So What (From the album “Kind of Blue). When does he hold a note and when is it short? How does this have an impact on the entire phrase and more importantly, what feeling does it evoke?

INTONATION

Essentially, intonation refers to the accuracy with which a note is played or sung—whether it’s slightly flat or sharp compared to the desired pitch. Jazz musicians leverage intonation as a tool for expression, infusing their performances with nuance and emotion. Without this attention to intonation, the music would lack vitality and authenticity, underscoring its importance in the swing vocabulary.

While initially hesitant to consider intonation as a component of swing, given its relevance to the pitch of the note rather than the rhythms, I soon realised its profound impact on expression and the spirit of the music. Essentially, intonation refers to the accuracy with which a pitch is played or sung – Whether it’s slightly flat (below the note) or sharp (above the note). Jazz musicians leverage intonation as a tool for expression, which adds to the emotion of the improvisation. Without this attention to intonation, the music would lack vitality and authenticity, which is an important aspect of improvisation. Listen to Lester Young play his iconic solo on Fine and Mellow (2:01)

Notice how Lester slides to notes and between notes. At 2:18 to 2:23 he plays a melodic line where he intentionally plays with intonation between two notes which blurs the line between sharp and flat: This gives the phrase something special, as you can see on Billie Holiday’s face!

Another example is Veronica Swift singing The Man I Love from her This Bitter Earth album. There are many examples throughout the performance, but a notable one is from 3:48 to 3:58. She uses intonation as a tool for expression on the words “Sure”, “Someday” and “Tuesday”, sliding between syllables.

TONE & EFFECTS

Beyond the notes and the rhythms themselves, a musician’s tone and use of effects contribute to the overall feel of the performance. This varies from instrument to instrument depending on the mechanics of what is being played, but generally speaking, the pitch that is being played (the fundamental frequency) can sound many different ways. It can sound warmer (or “lower” to some) or it can sound brighter. For example, if an alto saxophonist plays a concert C, this is going to sound different to if a guitarist plays a concert C. it is the same note, but the timbre (tone) is different.

Timbre can be modified to suit the expression of the song and a musician may choose to vary it from phrase to phrase or even note to note. This is done in different ways depending on the instrument. For example, guitarists may control attack with their hands and vary the way they play the notes. For amplified instruments, the player may adjust the EQ settings or add other effects. Singers modify tone internally by changing the shape of the vocal tract. Effects can be added by saxophonists such as growls. The list goes on.

PHRASING

This is again more relevant to the rhythms being played and not so much to do with the articulation or approach to note. However, it is still worthwhile to mention that phrasing can impact the way swing feels. Phrasing is the term we might use for where we are placing the melodic phrase in relation to the beats and the bars. It can also be a way to describe where the rhythmic phrase sits in relation to the subdivisions. For example, is it an exact triplet or does it feel “straighter” (closer to the eighth-notes). Are the notes played by the soloist behind the beat (slightly after the beat) or in front of the beat (slightly ahead of the beat). This is a complex topic though, so it can be explored in future blogs.

HOW TO PRACTICE

All the above being said, how does a musician learn these complicated skills and begin applying them to improvising? Below are some exercises you may like to explore.

Practicing time

Understanding the relationship between pulse and rhythm, commonly referred to as “time”, is essential for swinging. Musicians develop a vocabulary of rhythmic patterns and styles, knowing how specific rhythms sound within different contexts such as tempo (speed of the song) or groove. But if the musician doesn’t understand the relationship between the rhythms and the space in which they play them, something doesn’t feel right.

Understanding the relationship between pulse and rhythm, commonly referred to as “time”, is essential for swinging.

To understand the pulse and the rhythms within them, it is imperative to internalise them. This means to not only cognitively understand them, but to have the body and the ears understand. This can be done in many ways, but if you are just starting out, these exercises might help:

Clapping on certain beats

Clapping on beat one of each bar can be a useful strategy to really feel where time is. You can start with clapping on beat one, then add either singing the melody or singing another rhythmic pattern. If this is too easy, you can clap or tap your foot on beats 2 and 4, then when this feels comfortable add the melody. This can be done to your favourite Jazz recordings or to a metronome. If you need more time to figure out where beat 2 and 4 is in relation to the melody, you can start out of time and then add the metronome later in your practice.

Practicing different tempos

It is important to internalise these rhythms over different tempos. For example, a fast swing feels very different to a slow swing, and this will have an impact on articulation or the way you approach expression when playing/singing.

Listening and Imitation

One of the most effective ways to learn Jazz language is by listening to recordings of Jazz masters and imitating their articulation. By studying the nuances of their timing, articulation, and feel, musicians can absorb the language of Jazz and incorporate it into their own playing. You can start with a note-by-note approach. Stop the recording and sing or play back the note, trying to accurately imitate the duration, volume, attack, tone and anything else you can here. After this becomes comfortable, try an entire phrase, playing or singing the phrase until you get it as close as you can to what the artist plays.

SUMMARY

In summary, swing is the lifeblood of Jazz, driving its energy and expression. Mastering the nuances of swing requires a combination of technical skill, rhythmic sensitivity, and internalisation of language. By delving into the intricacies of swing and embracing the spirit of improvisation, musicians can unlock a freedom of improvisation they never knew possible and more importantly, experience the joy of playing Jazz.

If you’d like to learn more from Charlotte, check out JMI’s Bachelor and Diploma programs with auditions open for 2025 entry!