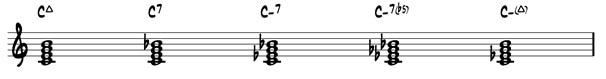

One of the first things you’ll learn in any tertiary contemporary music course – especially at JMI in Brisbane, once your fundamental scales and triads are secure, is how to “spell” 7th chords – not just dominant 7ths, but major and minor 7ths, diminished and half-diminished 7ths, and minor-major 7ths. You’ll be shown how to construct these by selecting the appropriate 3rd, 5th and 7th, and stacking them above the root. The resulting 1-3-5-7 constructions are called “chord spellings”.

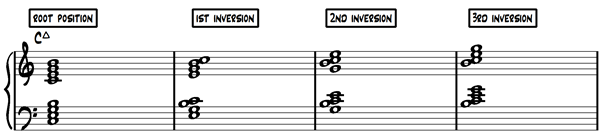

Next you’ll be shown three additional inversions of the spellings (3-5-7-1, 5-7-1-3 etc), and perhaps how to arrange progressions of inverted 7th chords so that the voice leading is smooth. And perhaps as you sit practicing these sequences, you’ll get the feeling that, no matter how good you get at this, it’s never going to sound like Bill Evans, or Art Tatum, or Corey Henry.

If you get that feeling, you’ll be absolutely right. It is almost impossible to find an example of any of the jazz piano players we love playing any of the chords arrived at from the “spelling” system. They avoid these chords for a very simple reason – they don’t like the way they sound! Please don’t misunderstand this. I’m not saying that these chords just aren’t sophisticated enough for jazz.

I’m saying that these chords sound so ugly that no one uses them anywhere, ever.

So why were you taught this? Because it’s crucial that you know what the ingredients of the various 7th chords are and how to derive them from scales. But, if you want to make a nice sound at the piano, you have to move past spellings.

Enter the concept of “voicing”, which simply means distributing the ingredients of the chord amongst voices, but has inherent in it the idea of arranging for the best effect. In the case of 7th chords, there’s a very simple rule of thumb that works, mostly. I recommend that you read the remainder of this while sitting at a piano, so you can try what I’m suggesting and hear the difference for yourself. (I’ve avoided giving notated examples so that you have to try it yourself.)

Start with the idea of playing a chord accompaniment in a song that doesn’t have 7th chords. You would play the roots of the chord in the bass register with your left hand, and some inversion of the triad with your right hand, (not too far from middle C for a warm tone). Now, here is the crux of the matter: to convert the triads to 7th chords, you are NOT going to add the 7th to everything you already have. You are going to locate the root in your right hand inversion, and REPLACE it with the appropriate 7th.

The resulting chord will almost always sound good, simply because there is only ever one root.

Why do I keep saying mostly, and almost? Because there is one exception, and it’s this. If you make a dominant 7th chord from the 1st inversion triad, by replacing the root in the right hand with the 7th as stated above, you will end up with something just as ugly as the original spelling. In fact, apart from the root being an octave or two lower, it is the original spelling, and yet this doesn’t matter in major 7ths or minor 7ths, just dominant 7ths.

The solution? When making a dominant 7th chord from a 1st inversion triad, replace the 5th with the 7th, and leave the root on top. (This will be your first experience of a mantra that I repeat over and over to piano students until they have it in their bones: No natural 5ths in dominant 7th chords.)

Still not sounding like Bill? Bill included extensions in his chords, a topic for another day. But at least now you’re making a pleasant sound.