HOW TO SOLO ON A JAZZ BLUES – PART 1

By Travis Jenkins, JMI lecturer

(Guitar, Jazz Materials, Ensemble, Jazz Composition)

For most musicians who have had some experience with improvising, the blues form is already something they will be fairly familiar with. The 12 bar blues form is one of the most recognisable song forms in popular music, transcending and permeating other genres of music while providing a ubiquitous template for narrative and improvisation. That the blues has continued to make (to varying degrees) such a lasting and influential impression on modern popular music is not surprising, especially considering the foundational nature of its influence on Jazz music in America in the early 20th century; (what became) the standard 12 bar chord form, and the melodic phrasing derived from early spirituals and work songs, being eventually accompanied and informed by more complex harmonic variations and rhythmic complexities that reflect the industrial and metropolitan growth of the times.

This harmonic complexity in particular is what can often prove to be quite challenging for those who are newcomers to the study of this beautiful modern art form and culture. In this article we hope to provide some starting points for those who are only just beginning to entertain their curiosities as improvisers, while also hopefully some new ideas for those already well on their journeys.

Before we get into it, there are a few things to consider first:

Listen!

When entering into a new creative foray, immersion is the key. You HAVE to listen to the recordings… Find a blues head that you love and see how many different recorded performances of it you can dig up. Practice active listening… Play the same recording on repeat for as many times as there are personnel in the ensemble, listening to each respective musician’s performance. Then listen some more! Perhaps on one playthrough, your focus is on the phrasing of a solo, then on the second playthrough the focus is on the articulation.. Listen often and listen deeply.

Sing!

Learn to sing the melodies and solos note for note. Singing helps us to internalise the music on a deeper level and makes the listening experience much more active and intuitively analytical.

Transcribe!

One of the best things that anyone can do for their musicality when studying any type of musical art form is to transcribe by ear from the recordings. It has so many beneficial learning outcomes from enhancing your aural comprehension, expanding your vocabulary of the musical language in the context of a performance, improving your sense of time, phrasing, tone, pitch, articulation.. And not to mention the countless benefits to be had from anaylsing what you’ve worked out to better understand how you can use the language in your own way. Transcribing is so important that you can almost afford to do little else toward your musical growth if you are fully committing yourself to being able to play in time with the recordings… almost.

Here we will look at 5 different approaches to soloing over a jazz blues while checking out some recorded examples along the way.

LEVEL 1 – Play the Melody…

By far one of the most overlooked improvisational devices that can be applied to any tune is to go directly to the source material.. the melody! There are countless blues heads that all share the same or similar form and chords, with the melody providing the only compositional distinction. Before busting out into an endless flurry of blues licks on your first B flat 7 chord at the top of the form, try rephrasing the melody or referencing it in your melodic ideas. The melodies often contain great blues phraseology and melodic information to expand your vocabulary. The more blues heads that you learn (in all keys), the more benefits you will get across all areas of your playing.

A great example of this approach is this Charlie Rouse solo on “Blue Monk”

Further to this, a lot can be said about using the idiomatic phrasing and melodic devices that epitomise the blues such as the use of repeated riffs, call-and-response, and the use of the blues scale…

This Miles Davis solo on “Blues by Five” has some excellent examples of call-and-response, repeated riffs and blues scale material.

LEVEL 2 – Blues Scales…

Historically, blues melodic phrasing is built from expressive uses and adaptations of pentatonic scales. These adaptations are what characterise the blues sound. You will no doubt be familiar with the term “blue notes”; ornamental pitches which are microtonal deviations from European 12-tone equal temperament. These sounds are easier to replicate on voice or on instruments which can bend in pitch, but need to be approximated on instruments which have fixed pitch like the piano. To do this we can turn the pentatonic scale into a hexatonic scale with the addition of a passing note.

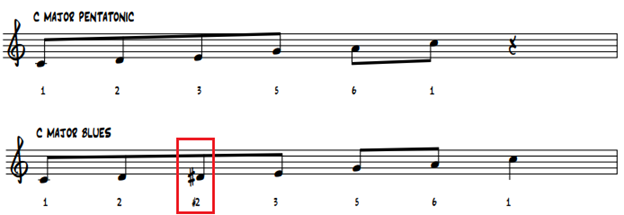

The major blues scale is derived from a passing note between the 2nd and 3rd:

While the minor blues scale is derived from a passing note between the 4th and 5th:

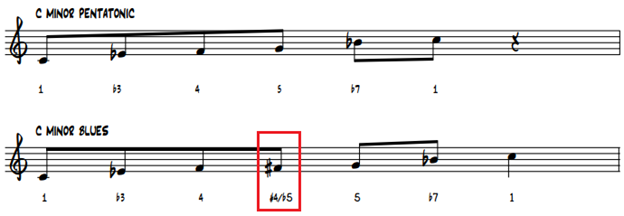

It is worth mentioning also, that the minor pentatonic scale is a mode of the major pentatonic scale; ie. playing the A minor pentatonic or A minor blues scale is essentially the same as playing the C major pentatonic or C major blues scale as they both share exactly the same pitches. But the use of both major and minor blues scales in parallel (ie. starting from the same note) works well over a jazz blues because of the inherent flexibility of dominant 7th chords.

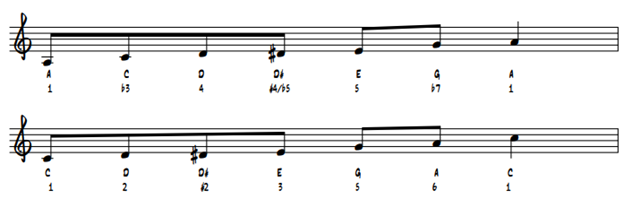

There are however some issues with using scales exclusively for improvisation. If we look at even the most basic blues chord changes we can see that some notes from either of the two scales are potentially not going to work as well on particular chords:

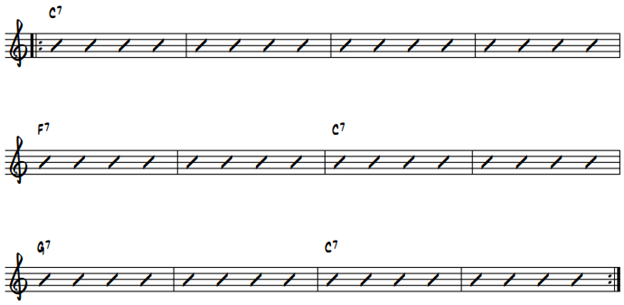

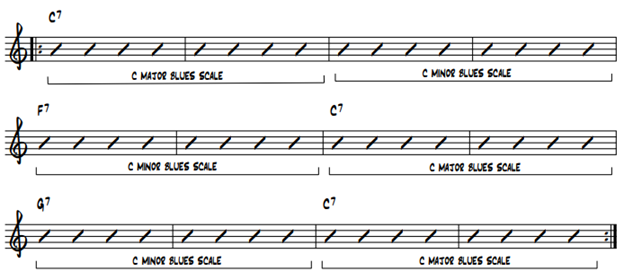

The E natural from the C major blues scale will not work so well over an F7 as it will clash with the flat 7th (E flat). Similarly, the F natural from the minor blues scale can sound a bit awkward over the C7 in some instances, clashing with the 3rd (E). The G7 has the issue of the C in both scales clashing with its 3rd (B). So you need to use your ear to find where these sounds “fit”. Try alternating between the major and minor blues scales at different points in the form to see what feels right and to get the sounds in your ears:

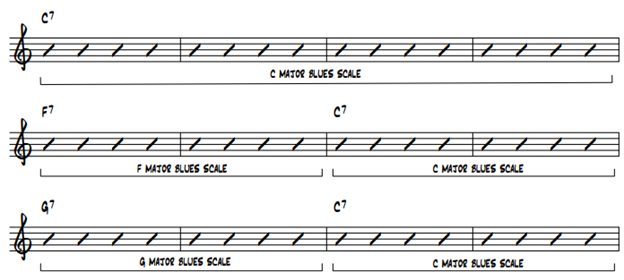

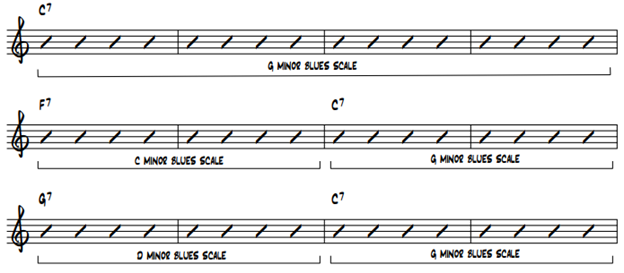

When you get a bit more comfortable with the scales, you can start applying them in different ways. For example, you could use the major blues scale from the tonic of each of the chords, or the minor blues scale from the 5th of each of the chords:

In the context of jazz harmony, this generalised approach to using scales might seem a bit harmonically reductive, but nonetheless, these are important melodic devices for improvisational phrasing on a blues. They just need to be handled with care…

Check out how Jackie McLean goes between using blues scale language and bebop language at different points in the form on his solo over “Cool Struttin’”